Teacher Trauma is one of those things that teachers joke about around the lunch table, but I don’t think people realize just real it is. I’ve been out of the classroom for two years and still feel it at work and everyday life. The guilt and shame I feel in sharing fills my heart with dread. My traumatized brain tells me I should have been stronger, that silence is strength, shut up and suck it up. But those of you who are in the classroom and those who have left were strong enough. You were enough. Your experiences are real. The people who laugh at TFA fails or tell teachers, “if you don’t like it, quit,” have no standing to tell you what you should feel. Your AP and Principal either.

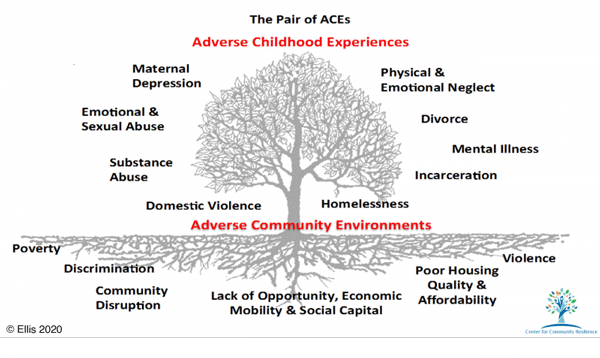

For those of you who don’t know: What is teacher trauma? Teacher trauma is the end result of repeated abuse in the classroom and other systemic violence on behalf of the public school system. In my experience, it is more prevalent in Title I teachers. A Title I school is a school that receives federally funding due to a high concentration of poverty in the attending families. It is not often contested that high-poverty area often experiences trauma at disproportionate rates to their more affluent peers. That is not to suggest that their affluent peers do not experience trauma; poverty merely increases the number of trauma exposures, whether that be to food insecurity, homelessness, familial drug use, police disturbances, domestic violence, neglect, etc.

The documentary “Resilience: The Biology of Stress and Hope” documents how Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) impact children. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur during childhood between (0-17). It is estimated that 60% of children experience at least one ACE in their lifetime. Demographically, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health:

National percentages of children experiencing at least one ACE include:

- 61 percent non-Hispanic Black children

- 51 percent of Hispanic children

- 40 percent non-Hispanic white children

- 23 percent non-Hispanic Asian children

Children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships. They may also have unstable work histories as adults and struggle with finances, jobs, and depression throughout life. These effects can also be passed on to their own children. In the classroom, students who have four or more ACEs struggle with attendance, behavior, and engagement. In a 2016 study

- 48% reported low engagement in school

- 44% had trouble staying calm and controlled in the classroom

- 49% had difficulties finishing the tasks

- 23% were diagnosed with a learning disability

Imagine 44% of your co-workers having trouble staying calm and controlled in your work environment. Imagine having little to no experience and guidance in emotional regulation and limited social awareness. Adults are expected to have self-control; children are not. Highly concentrated poverty correlates with highly concentrated ACEs. Students still seek to connect with their peers. And although they struggle to communicate and socialize with their peers, collective anger, feelings of being out of control, and resentment becomes a catalyst for connection among children. For the students, adults are oftentimes associated with their trauma; therefore, we must rage against the machine. The result is a war against their teachers. To validate their experience, power etc., they then recruit other students and foster an us-versus-them environment. Administrators often attribute this to “poor class management” or an “unsafe environment.” We often forget about children’s agency and youth culture’s strength.

It all comes down to one problem. There are more students than there are teachers. There are no resources, no counselors, nothing; it’s you and them. All of that pent-up rage and sadness goes somewhere. Imagine 44% of the people on your job were aggressive, not passive-aggressively, AGGRESSIVELY, reacting viscerally to every inconvenience, had zero to no impulse control, could not hear feedback without feeling like it was a personal attack and lashed out at you. That is the life of a Title I teacher. Could you get your job done? Would you want them walking around the office? Would you want to see them in the bathroom alone? Would you have productive meetings? People outside of education get hung up on “stay in your seat” lines and scheduled bathroom breaks. As a teacher, I protect your child when I say stay in your seat. I mean it when I say I have seen children get up and sharpen their pencils and slap another child on the way. I know it was not out of malice. When I asked them why they did it, they said, “I don’t know.” I knew they genuinely did not know why. But that is someone’s child so stay in your seat. I have sent kids to the bathroom and heard them yelling at another child and separated fights. In line, I can see when they step out to hurt someone. I have had children grab ME and say, “you’re not listening.” I know that was informed by their own trauma, but it was scary nonetheless. I have had students tell me, “you have a fat ol’ ass,” or hug me forcibly, although I had a strict no-hugging rule. I knew they had experienced sexual abuse. It did not change the fact that I was afraid for my job and, at 13-16, what would happen if they caught me alone in my classroom or a stairwell or their peers. I have had kids stand on the desk yelling fuck you bitch, and then huddled in the corner asking do you love me in the most hurt, whispered tone in the span of 10 minutes. Students are suffering, and as a teacher, I had so little to deal with it, especially since it was over half my students.

Not only were my students suffering, but the school created an atmosphere in which I was also forced to suffer. During my first experience in teaching, I got a kidney infection. We were told if you needed to go to the bathroom, call the office, and you would be relieved. I was told I called too often and to try and limit my bathroom breaks, “we need you to be present and available to your kids.” So I stopped drinking water, and held it ’til I thought my bladder would break. You get one planning block; most of the time, you have to cover no sub-classes. Lunch is 20 minutes, but you only get 15 after walking your kids to the cafeteria. If I went to the bathroom, I didn’t eat. And at the end of the day, when I would sprint to the toilet after the bell, I would be reprimanded for not being at my duty post. I was peeing blood, antibiotics weren’t working, and I landed in the hospital with a 104-degree fever. When I was out at the doctor, they asked me if I could please come in if it “wasn’t that serious.”

Those examples are traumatic. If these were adult-adult exchanges in any other professional environment, you would expect your managers to respond and react. In the adult-adult exchange, I mentioned if kids weren’t involved, most people would say it was an injustice. Regardless, it was an injustice. I should not have been asked to choose between my health and my students. When dealing with multiple children’s trauma created my own. It was made personal. The call of the teacher is to be resourceful and resilient. In retrospect and actuality, it is to accept and ignore, to do more with less. There is a problem in our educational system. If the goal is to create college and career-ready citizens, ACEs fall under the realm of responsibility of education. But it is not the teachers’ responsibility to “manage” students’ trauma response. A new need is emerging in schools that must be addressed outside the conventional educational service lines.